After Actium and the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, Octavian was in a position to rule the entire Republic under an unofficial principate, but would have to achieve this through incremental power gains, courting the Senate and the people, while upholding the republican traditions of Rome, to appear that he was not aspiring to dictatorship or monarchy. Marching into Rome, Octavian and Marcus Agrippa were elected as dual consuls by the Senate. Years of civil war had left Rome in a state of near lawlessness, but the Republic was not prepared to accept the control of Octavian as a despot. At the same time, Octavian could not simply give up his authority without risking further civil wars amongst the Roman generals, and even if he desired no position of authority whatsoever, his position demanded that he look to the well-being of the city of Rome and the Roman provinces. Octavian's aims from this point forward were to return Rome to a state of stability, traditional legality and civility by lifting the overt political pressure imposed on the courts of law and ensuring free elections in name at least.

First settlement

Main articles: Constitution of the Roman Empire and History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire

Although Octavian was no longer in direct control of the provinces and their armies, he retained the loyalty of active duty soldiers and veterans alike. The careers of many clients and adherents depended on his patronage, as his financial power in the Roman Republic was unrivaled. The historian Werner Eck states:

The sum of his power derived first of all from various powers of office delegated to him by the Senate and people, secondly from his immense private fortune, and thirdly from numerous patron-client relationships he established with individuals and groups throughout the Empire. All of them taken together formed the basis of his auctoritas, which he himself emphasized as the foundation of his political actions.To a large extent the public was aware of the vast financial resources Augustus commanded. When he failed to encourage enough senators to finance the building and maintenance of networks of roads in Italy, he undertook direct responsibility for them in 20 BC. This was publicized on the Roman currency issued in 16 BC, after he donated vast amounts of money to the aerarium Saturni, the public treasury.

According to H.H. Scullard, however, Augustus's power was based on the exercise of "a predominant military power and [...] the ultimate sanction of his authority was force, however much the fact was disguised."

The Senate proposed to Octavian, the victor of Rome's civil wars, that he once again assume command of the provinces. The senate's proposal was a ratification of Octavian's extra-constitutional power. Through the senate Octavian was able to continue the appearance of a still-functional constitution. Feigning reluctance, he accepted a ten-year responsibility of overseeing provinces that were considered chaotic. The provinces ceded to him, that he might pacify them within the promised ten-year period, comprised much of the conquered Roman world, including all of Hispania and Gaul, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus, and Egypt. Moreover, command of these provinces provided Octavian with control over the majority of Rome's legions.

While Octavian acted as consul in Rome, he dispatched senators to the provinces under his command as his representatives to manage provincial affairs and ensure his orders were carried out. On the other hand, the provinces not under Octavian's control were overseen by governors chosen by the Roman Senate. Octavian became the most powerful political figure in the city of Rome and in most of its provinces, but did not have sole monopoly on political and martial power. The Senate still controlled North Africa, an important regional producer of grain, as well as Illyria and Macedonia, two martially strategic regions with several legions. However, with control of only five or six legions distributed amongst three senatorial proconsuls, compared to the twenty legions under the control of Augustus, the Senate's control of these regions did not amount to any political or martial challenge to Octavian. The Senate's control over some of the Roman provinces helped maintain a republican façade for the autocratic Principate. Also, Octavian's control of entire provinces for the objective of securing peace and creating stability followed Republican-era precedents, in which such prominent Romans as Pompey had been granted similar military powers in times of crisis and instability.

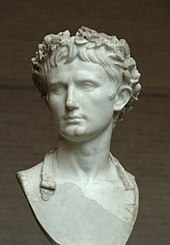

In January of 27 BC, the Senate gave Octavian the new titles of Augustus and Princeps. Augustus, from the Latin word Augere (meaning to increase), can be translated as "the illustrious one". It was a title of religious rather than political authority. According to Roman religious beliefs, the title symbolized a stamp of authority over humanity—and in fact nature—that went beyond any constitutional definition of his status. After the harsh methods employed in consolidating his control, the change in name would also serve to demarcate his benign reign as Augustus from his reign of terror as Octavian. His new title of Augustus was also more favorable than Romulus, the previous one he styled for himself in reference to the story of Romulus and Remus (founders of Rome), which would symbolize a second founding of Rome. However, the title of Romulus was associated too strongly with notions of monarchy and kingship, an image Octavian tried to avoid. Princeps, comes from the Latin phrase primum caput, "the first head", originally meaning the oldest or most distinguished senator whose name would appear first on the senatorial roster; in the case of Augustus it became an almost regnal title for a leader who was first in charge. Princeps had also been a title under the Republic for those who had served the state well; for example, Pompey had held the title. Augustus also styled himself as Imperator Caesar divi filius, "Commander Caesar son of the deified one". With this title he not only boasted his familial link to deified Julius Caesar, but the use of Imperator signified a permanent link to the Roman tradition of victory. The word Caesar was merely a cognomen for one branch of the Julian family, yet Augustus transformed Caesar into a new family line that began with him.

Augustus was granted the right to hang the corona civica, the "civic crown" made from oak, above his door and have laurels drape his doorposts. This crown was usually held above the head of a Roman general during a triumph, with the individual holding the crown charged to continually repeat "memento mori", or, "Remember, you are mortal", to the triumphant general. Additionally, laurel wreaths were important in several state ceremonies, and crowns of laurel were rewarded to champions of athletic, racing, and dramatic contests. Thus, both the laurel and the oak were integral symbols of Roman religion and statecraft; placing them on Augustus' doorposts was tantamount to declaring his home the capital. However, Augustus renounced flaunting insignia of power such as holding a scepter, wearing a diadem, or wearing the golden crown and purple toga of his predecessor Julius Caesar. If he refused to symbolize his power by donning and bearing these items on his person, the Senate nonetheless awarded him with a golden shield displayed in the meeting hall of the Curia, bearing the inscription virtus, pietas, clementia, iustitia—"valor, piety, clemency, and justice."

Second settlement

In 23 BC, there was a political crisis that involved Augustus' co-consul Terentius Varro Murena, who was part of a conspiracy against Augustus. The exact details of the conspiracy are unknown, yet Murena did not serve a full term as consul before Calpurnius Piso was elected to replace him. Piso was a well known member of the republican faction, and serving as co-consul with him was another means by Augustus to show his willingness to make concessions and cooperate with all political parties. In the late spring Augustus suffered a severe illness, and on his supposed deathbed made arrangements that would put in doubt the senators' suspicions of his anti-republicanism. Augustus prepared to hand down his signet ring to his favored general Agrippa. However, Augustus handed over to his co-consul Piso all of his official documents, an account of public finances, and authority over listed troops in the provinces while Augustus' supposedly favored nephew Marcus Claudius Marcellus came away empty-handed. This was a surprise to many who believed Augustus would have named an heir to his position as an unofficial emperor. Augustus bestowed only properties and possessions to his designated heirs, as a system of institutionalized imperial inheritance would have provoked resistance and hostility amongst the republican-minded Romans fearful of monarchy.Soon after his bout of illness subsided, Augustus gave up his permanent consulship. The only other times Augustus would serve as consul would be in the years 5 and 2 BC. Although he had resigned as consul, Augustus retained his consular imperium, leading to a second compromise between him and the Senate known as the Second Settlement. This was a clever ploy by Augustus; by stepping down as one of two consuls, this allowed aspiring senators a better chance to fill that position, while at the same time Augustus could "exercise wider patronage within the senatorial class." Augustus was no longer in an official position to rule the state, yet his dominant position over the Roman provinces remained unchanged as he became a proconsul. Earlier as a consul he had the power to intervene, when he deemed necessary, with the affairs of provincial proconsuls appointed by the Senate. As a proconsul Augustus did not want this authority of overriding provincial governors to be stripped from him, so imperium proconsulare maius, or "power over all the proconsuls" was granted to Augustus by the Senate.

Augustus was also granted the power of a tribune (tribunicia potestas) for life, though not the official title of tribune. Legally it was closed to patricians, a status that Augustus had acquired years ago when adopted by Julius Caesar. This allowed him to convene the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and the right to speak first at any meeting. Also included in Augustus' tribunician authority were powers usually reserved for the Roman censor; these included the right to supervise public morals and scrutinize laws to ensure they were in the public interest, as well as the ability to hold a census and determine the membership of the Senate. With the powers of a censor, Augustus appealed to virtues of Roman patriotism by banning all other attire besides the classic toga while entering the Forum. There was no precedent within the Roman system for combining the powers of the tribune and the censor into a single position, nor was Augustus ever elected to the office of censor. Julius Caesar had been granted similar powers, wherein he was charged with supervising the morals of the state, however this position did not extend to the censor's ability to hold a census and determine the Senate's roster. The office of the tribune plebis began to lose its prestige due to Augustus' amassing of tribunal powers, so he revived its importance by making it a mandatory appointment for any plebeian desiring the praetorship.

In addition to tribunician authority, Augustus was granted sole imperium within the city of Rome itself: all armed forces in the city, formerly under the control of the prefects and consuls, were now under the sole authority of Augustus. With maius imperium proconsulare, Augustus was the only individual able to receive a triumph as he was ostensibly the head of every Roman army. In 19 BC, Lucius Cornelius Balbus, governor of Africa and conqueror of the Garamantes, was the first man of provincial origin to receive this award, as well as the last. For every following Roman victory the credit was given to Augustus, because Rome's armies were commanded by the legatus, who were deputies of the princeps in the provinces. Augustus' eldest son by marriage to Livia, Tiberius, was the only exception to this rule when he received a triumph for victories in Germania in 7 BC. Ensuring that his status of maius imperium proconsulare was renewed in 13 BC, Augustus stayed in Rome during the renewal process and provided veterans with lavish donations to gain their support.

Many of the political subtleties of the Second Settlement seem to have evaded the comprehension of the Plebeian class. When Augustus failed to stand for election as consul in 22 BC, fears arose once again that Augustus was being forced from power by the aristocratic Senate. In 22, 21, and 19 BC, the people rioted in response, and only allowed a single consul to be elected for each of those years, ostensibly to leave the other position open for Augustus. In 22 BC there was a food shortage in Rome which sparked panic, while many urban plebs called for Augustus to take on dictatorial powers to personally oversee the crisis. After a theatrical display of refusal before the Senate, Augustus finally accepted authority over Rome's grain supply "by virtue of his proconsular imperium", and ended the crisis almost immediately. It was not until AD 8 that a food crisis of this sort prompted Augustus to establish a praefectus annonae, a permanent prefect who was in charge of procuring food supplies for Rome. In 19 BC, the Senate voted to allow Augustus to wear the consul's insignia in public and before the Senate, as well as sit in the symbolic chair between the two consuls and hold the fasces, an emblem of consular authority. Like his tribune authority, the granting of consular powers to him was another instance of holding power of offices he did not actually hold. This seems to have assuaged the populace; regardless of whether or not Augustus was actually a consul, the importance was that he appeared as one before the people. On 6 March 12 BC, after the death of Lepidus, he additionally took up the position of pontifex maximus, the high priest of the collegium of the Pontifices, the most important position in Roman religion. On 5 February 2 BC, Augustus was also given the title pater patriae, or "father of the country".

Later Roman Emperors would generally be limited to the powers and titles originally granted to Augustus, though often, to display humility, newly appointed Emperors would decline one or more of the honorifics given to Augustus. Just as often, as their reign progressed, Emperors would appropriate all of the titles, regardless of whether they had actually been granted them by the Senate. The civic crown, which later Emperors took to actually wearing, consular insignia, and later the purple robes of a Triumphant general (toga picta) became the imperial insignia well into the Byzantine era.

0 comments:

Post a Comment